15 9. The conservation of Dd.4.24 by Kristine Rose

The conservation of Cambridge University Library’s oldest Chaucer manuscript, Dd.4.24, began in 2004. The binding, full brown calf and dated 1872, was in poor condition. Both boards were loose and the leather was abraded at the corners. The spine leather was scuffed at the head and tail, and the tail cap was almost detached. The binding was no longer supporting the manuscript and the covering leather had begun to stain the endpapers. The boards did hold evidence of an earlier binding; a small square of brown leather (gold tooled with a central acorn and oak leaf design and flanked by blind-tooled initials S and W) was adhered on the inside of both boards.

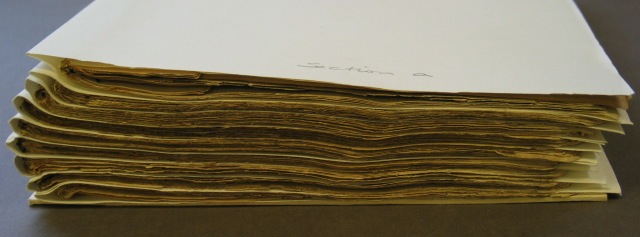

To allow for conservation and for complete digitisation of the text block, the manuscript was disbound by senior Conservator, Janet Coleby. It was removed from its 19th century binding and separated into nine quires (figure 1).

Figure 1: Dd.4.24 disbound

The 216-page text block consisted of 149 original manuscript paper leaves, 31 original parchment leaves, 7 new blank parchment leaves and 29 new blank paper stubs.[1] These stubs were heavy, inflexible and at only 50mm wide placed unnecessary stress upon the rest of the text block through the application of uneven pressure across the pages; More at the spine and none at the foredge, leading to a distorted text block profile. Otherwise, the original components of the manuscript were in reasonably sound condition. Both the paper and parchment were affected by surface dirt.

However, the major physical damage to the manuscript paper was caused by mould. This damage afflicted the entire text block. and although it was mostly restricted to the top quarter of the leaves, the first quire was particularly badly affected and had also suffered significant damage across the lower part. The paper leaves were soft and fragmentary in the mould-damaged areas and torn and worn along the heavily used leaf edges.

The first treatment for the manuscript was the removal of heavy aged glue from the spine edge of the nine quires. This was facilitated by the use of a wheat starch poultice and gave the pages more flexibility and allowed the quires to be taken down safely. The outermost parchment bifolia were most severely affected by the glue, but once this was removed, it was apparent they had suffered little damage.

With the manuscript separated into its component parts, the exact collation could be established and the page numbering checked. The manuscript could now be treated as individual folios.

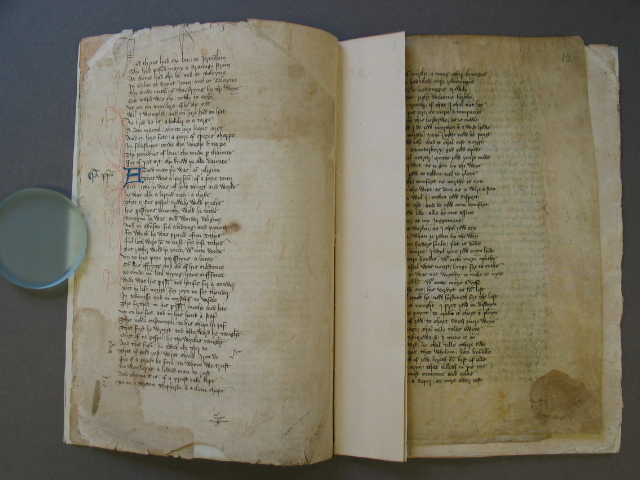

Figure 2: An opening within Dd.4.24 showing manuscript paper (left), new paper guards (centre) and manuscript parchment (right).

Previous detrimental repairs were removed throughout the manuscript. The short paper guards, which created uneven pressure and a variety of paper supports to tears and edges, were too heavy and obtrusive. These were removed mechanically, once again with the aid of a wheat starch poultice. Once all of the previous repairs were removed mechanical surface cleaning was carried out. This process, a combination of chemical smoke sponge and grated Mars Plastic Eraser™, was carried out carefully around the most severely damaged areas of the manuscript, which were too weak to clean comprehensively. Care was also taken not to further destabilise the weak pigment of the illuminated capitals throughout the text, and the various wax accretions spread across several of the pages were left intact.

Before the paper folios could be repaired, the mould-weakened areas were strengthened. Localised application of a 2% gelatine size substantially improved the integrity of the paper. Applied with an Ultrasonic mister, the vaporised size was drawn into the weak areas of the folios on a suction table. After application, the folios were allowed to dry in-situ to avoid any risk of tidemarks.

Now ready for repair, losses and tears to the individual paper leaves were supported with Japanese handmade papers- Usimino (14gsm) and Tengujo (8gsm). These repair papers were needled out over a light box to ensure an exact fit to the lost areas and to create a fibrous edge for the strongest bond between the new repair and the original object. They were then applied with wheat starch paste to ensure full reversibility, and dried between woollen felts to avoid cockling.

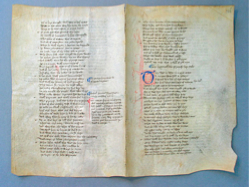

The original parchment manuscript leaves were then treated. The folios were carefully cleaned with chemical smoke sponge in readiness for humidification (figure 3).

Figure 3: 156 recto/ 157 verso before humidification

A humidification chamber was prepared and the folios were individually relaxed. By re-introducing moisture to the parchment in this controlled way it was possible to avoid any fugitivity of the blue and red capitals. The moisture also increases the flexibility of the parchment and aids in the removal of distortions caused by physical stresses and fluctuations in environmental conditions. After this time, the pages were removed from the chamber and air dried under light tension before being repaired with Japanese papers in the same way as the paper folios. Having repaired and stabilised the original manuscript pages, attention could now be given to binding the manuscript. Due to the number of missing pages, previously indicated with heavy paper guards, the decision was taken to make complete new folios for the manuscript. A total of nine new bifolios and twelve individual folios were required to complete the paper manuscript,[2] with another four single folios and two bifolios to complete the parchment quire.

The replacement parchment leaves were joined to the original manuscript with wheat starch paste, however, in order to create the most aesthetically pleasing paper pages a suitable conservation standard handmade paper needed to be found.

The paper needed to match the original pages in tone, weight and texture. It also needed to be a laid paper with a chain pattern as close to that of the original as possible. This was supplied by Griffen Mill who, after extensive discussion and the exchange of numerous samples, were able to provide a small run of custom-made paper specifically for Dd.4.24. This paper, based loosely on one of their standard products, Samarqand, was used to make up the missing body of the manuscript. The replacement leaves ensure the manuscript will appear cohesive to the scholars using it, whilst also preventing the uneven distribution of pressure that had caused distortion of the 1872 binding.

Having replaced the paper stubs with the new Griffen Mill bifolia, fifteen paper manuscript leaves required the addition of new paper to make them into a complete bifolium. Rather than attaching the new paper directly to the original manuscript paper, an inlay technique was used. This technique avoids stress between the weaker manuscript paper and the new repair paper. The new paper was cut and shaped to follow the contour of the manuscript edge but then a small space of less than one millimetre was left between the two pieces. The two folios were joined with small strips of Usimino (14gsm) and Tengujo. The use of Japanese paper between the new and original elements of the manuscript ensures they will not fight against each other and incur damage. With all of the original manuscript bifolia conserved, the parchment and paper leaves were re-integrated and the manuscript was ready for binding.

Although Dd.4.24 consists of just nine quires, each quire contains 12 bifolia. The weight and size of the paper and parchment combination creates a number of challenges for the binder. Firstly, the quires are particularly thick. For this reason they benefit from a packed sewing structure. This structure adds support and control to the spine area, so the codex will open evenly at any point without undue stress on the sewing or manuscript pages.

The use of double cord sewing supports, typical throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, facilitates this structured form of sewing. Secondly, the composite nature of the quires creates some anomalies in the way they behave when handled. Whilst paper is receptive to the binder’s methods of forming the codex, parchment can revolt against the constraints of folding (into a bifolium) and compressing (whilst sewing). Taking these factors into consideration it was possible to sew the manuscript once the quires had been guarded and tacketted.

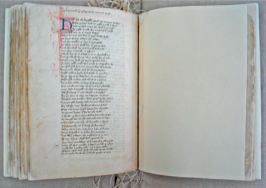

Figure 4: The sewn manuscript, awaiting boards and covering, with repaired manuscript paper (left) and the Japanese paper join to new Griffen Mill paper (right)

Dd.4.24 now awaits the final stages of binding (figure 4). It will probably be covered with alum-tawed skin and sewn with a traditional Triple Crown endband to join the spine to the covering. It will then be housed in a drop back box, alongside its previous binding, before being returned to the manuscript department and being made available to readers.